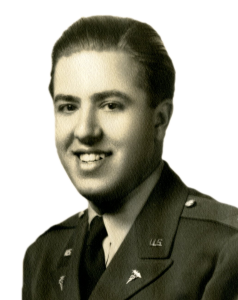

Here – on April 16, 1945, is Part One of an entry from the journal of Dr. Philip Westdahl about his “good fortune to take part in one of those rare experiences of drama in every-day life.” Part Two will be published on April 17.

Here – on April 16, 1945, is Part One of an entry from the journal of Dr. Philip Westdahl about his “good fortune to take part in one of those rare experiences of drama in every-day life.” Part Two will be published on April 17.

We were enjoying the sunset one evening when two small observation planes circled over the hospital area and dropped a message requesting us to halt traffic on the Autobahn in order that they might come in for an emergency landing. This was accomplished without difficulty and both planes made an easy landing and taxied off the highway into our hospital road. It was an exciting event for the 59th and all the personnel and those patients who could walk turned out to witness it.

A young air corps captain stepped out of the lead plane and immediately conveyed a message to the Colonel. A young American soldier lay critically ill in a German hospital in Heidelberg in need of a surgeon as soon as possible. I was fortunate to be the first one there to volunteer and within a few minutes Col. Mathewson [Mattie] our chief of surgery, and I, were each in a plane taking off on the highway. We took with us several bottles of blood and a few essential instruments, even though we heard that the German hospital was well equipped.

We flew southeast over the course of the autobahn, at an altitude of about 1000 feet. It was a beautiful sight to see the partially plowed fields below. They reminded me of a huge green and brown patchwork quilt. Here and there a farmer with horse and plow appeared as miniatures, moving slowly along in straight parallel rows, diverting every now and then to avoid a bomb or shell crater. From the air [these craters] look like the pictures one sees of the volcanoes on the moon. Our course took us over the German industrial cities of Frankenthal, Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. I have described these cities as their appeared from the road, but looking down on them from the air, the completeness of their destruction was even more evident. I had difficulty in finding a single square block of intact buildings.

We landed in a wheat field close to Heidelberg and were met by a jeep which took us immediately to the hospital. Heidelberg is a famous medical and university city and large red crosses were painted on the roofs of numerous hospital buildings in the various parts of the city. There was no evidence of damage to any part of it. We arrived at the hospital and were shown to the room of the only American soldier there. We could see at a glance that he was extremely ill, being markedly emaciated and as white as the sheet he was lying on. The German medical officer who had been caring for him was also present in the room and gave us a very complete account of the boy’s course.

We learned that the lad had been wounded on January 18th when his company was cut off by a German counterattack in the vicinity of Sarrebourg. He had been shot through the right hip, apparently producing a compound fracture of his femur and hip joint. He was captured by the Germans and taken to a German hospital in Sarrebourg. He was evacuated by train to Heidelberg on February 2. His hip joint had become badly infected, necessitating the removal of the upper end of his femur. He later developed a purulent infection of his ankle joint, which had to be opened and drained. His latest complication had been repeated massive hemorrhage from his hip wound, the last of which had occurred the morning of the evening we arrived. An American medical officer who had been inspecting all German military hospitals for American wounded had discovered this boy and immediately called for an American Army surgeon. [To be continued…]

.